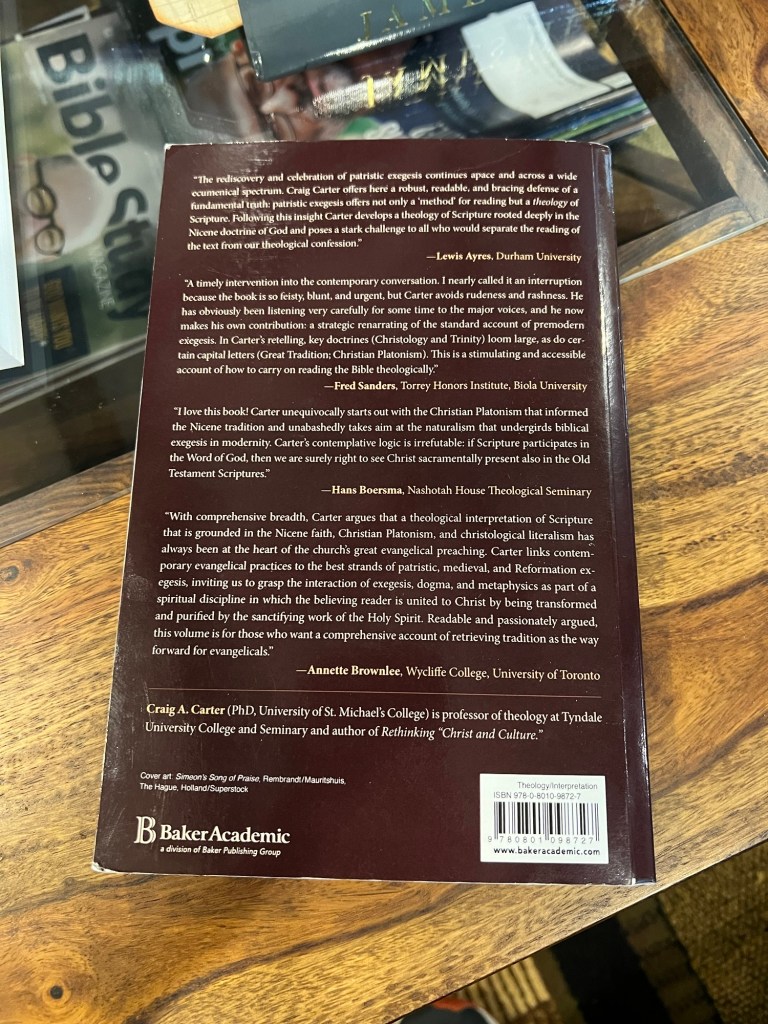

Carter, Craig A. Interpreting Scripture with the Great Tradition: Recovering the Genius of Premodern Exegesis. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2018. 304 pp. $26.49. 978-0801098727

Available From (click to access and purchase):

The Sword and Trowel Bookstore (Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary)

Biographical Sketch of the Author

Dr. Craig Carter currently serves as a Research Professor of Theology at Tyndale University of Toronto, Ontario. Dr. Carter’s primary teaching areas include systematic theology, historical theology, and Christian ethics. Prior to beginning his academic career, he served as pastor of several Baptist churches located in New Brunswick. He previously taught Philosophy and Religious Students at Crandall University. In addition to his distinguished teaching career, Carter served in academic administration as a Vice President and Academic Dean at Crandall University, and also held the same roles at Tyndale University College. In 2004, he returned to the classroom and has taught full-time since.[1]

Dr. Carter is a distinguished author of numerous works. In addition to the work reviewed in this post, he wrote Rethinking Christ and Culture: A Post-Christendom Perspective (Baker Books, 2007), The Faith Once Delivered: An Introduction to the Basics of the Christian Faith: An Exposition of the Westney Catechism (Baker Books, 2018), and Contemplating God with the Great Tradition: Recovering Trinitarian Classical Theism (Baker Books, 2021). He is also the author of numerous articles and reviews featured in several publications.[2]

Dr. Carter earned an Associate of Arts degree from Atlantic Baptist College in 1976, followed by a Bachelor of Arts (Hons.) from Mount Allison University in 1979. He then attended seminary at Acadia Divinity College of Acadia University, earning a Master of Divinity degree in 1983. He completed his Doctor of Philosophy degree at the University of St. Michael’s College, Toronto, in 1999.[3]

Overview

In Interpreting Scripture with the Great Tradition: Recovering the Genius of Premodern Exegesis, Carter advances the thesis that modern critical scholarship fails to fully account for the true meaning of Scripture and that a recovery of the Great Tradition reading of Scripture is necessary for the advance of the Gospel, strengthening of the church, and accurate understanding of God’s revelation of Himself. Carter identifies his purpose in writing as an attempt to restore the delicate but crucial balance between “biblical exegesis, trinitarian dogma, and theological metaphysics that was upset by the heretical, one-sided, narrow-minded movement that is misnamed ‘the Enlightenment,’” along with recovery of pro-Nicene theology and culture (26). In the first part of the book, Carter provides a critique of modern hermeneutics, specifically the historical-critical method of interpretation (Chs. 2-4). In the second part, Carter provides an articulation of the resources provided by the Great Tradition of scriptural exegesis that empower Christians to rightly interpret the Bible as the Word of God.

Structure and Critical Review

Carter’s work is divided into two major parts with a substantial introduction and conclusion. In the Introduction, Chapter 1, “Who Is the Suffering Servant? The Crisis in Contemporary Hermeneutics,” explores the gulf between modern hermeneutics and Christian preaching, the causes of that gulf, and promising developments offering opportunities for overcoming that gulf (3-30). In “Part 1: Theological Hermeneutics,” Carter employs Chapters 2-4 to explore the foundations of theological hermeneutics and the lay the foundations for the argument he advanced in Part 2. In Chapter 2, “Theological Hermeneutics,” Carter explored the inspiration of Scripture and how an understanding of the doctrine of inspiration impacts and shapes biblical hermeneutics. As Carter noted at the onset of Chapter 2, “This chapter is foundational to my entire proposal” (31). In Chapter 3, “The Theological Metaphysics of the Great Tradition,” Carter continues to advance the foundations of his proposal by exploring theological metaphysics and Christian Platonism (61-92). Carter argues that Christian Platonic thought is fundamental to the Great Tradition and deeply ingrained with the church’s history of biblical interpretation. In Chapter 4, “The History of Biblical Interpretation Reconsidered,” Carter explores and compares the exegesis of Scripture in the Great Tradition, as well as in modernity, and evaluates how the narrative of Scriptural exegesis should be revised in the present age.

In “Part 2: Recovering Premodern Exegesis,” Carter advances his proposal for a recovery of the Great Tradition of interpreting Scripture in Chapters 5-7. In Chapter 5, “Reading the Bible as Unity Centered on Jesus Christ,” Carter explores the hermeneutical contributions of Ambrose of Milan, Justin Martyr, and Irenaeus (129-160). These early fathers of the church modeled biblical interpretation as a spiritual discipline, the apostles as models in biblical interpretation, and the rule of faith as the guide for interpreting Scripture, respectively. In Chapter 6, “Letting the Literal Sense Control All Meaning,” the author explores Augustine’s assertion that the spiritual meaning of Scripture flows out of the literal sense of Scripture, as well as the argument that all meaning is contained in the plain sense of Scripture (161-190). Finally, in Chapter 7, “Seeing and Hearing Christ in the Old Testament,” Carter provided a primer on prosopological exegesis, explored Augustine’s Christological interpretation of the Psalms, and the “Christological literalism of the Great Tradition as scientific exegesis” (191-225). The work then concludes with Chapter 8, “The Identity of the Suffering Servant Revisited,” using Isaiah 53 as a case study for applying the Great Tradition paradigm of Scriptural interpretation against the modern perspective (227-254).

Among the most powerful and notable points provided by the work are Carter’s summary and analysis of Christian Platonism and the crucial role of Christian Platonism throughout the history of the church and biblical interpretation within the church. In Chapter 3, Carter examined the rejection of Christian Platonic metaphysics by the Enlightenment. There, he also convincingly argues that a helpful understanding of a biblical doctrine of God afforded by Christian Platonic metaphysics was exchanged for the chronic instability, methodological fragmentation, increasing relativism, and silencing of the Bible within churches brought on by the historical-critical method of interpretation (22-23; 84-91).

Critical Evaluation and General Reaction

My general reaction is one of appreciation for Carter’s points and analysis, as well as broad agreement with his purpose, approach, and conclusions. I share his disdain for the errors of the historical-critical method of Scriptural interpretation that rose to prominence as an aftershock of the Enlightenment, as well as his grief over the tragic and destructive consequences produced by this hermeneutic within the church. As a pastor, I find myself better equipped to advance my concerns and defend my opposition to historical-critical approach as a consequence of reading this book.

Carter also provides a helpful articulation of the vital relationship between the doctrine of God, the doctrine of Scripture, and hermeneutics as the study of how to interpret Scripture. Carter summarized, “As Webster pithily expresses it, ‘bibliology is prior to hermeneutics.’ But, as he also pointed out, bibliology itself cannot be the starting point; the nature of the text is inseparable from the res of the text, its subject matter and substance” (33). Carter continued, “Bibliology is the account of God speaking through the text, so bibliology itself must be grounded within he doctrine of God. We do not really know what the Bible is until we know who it is who commandeers these human words and reveals himself through them” (33).

Hermeneutics, bibliology, and the doctrine of God are all undeniably related and necessary to a full understanding of Scripture. Carter acknowledged that there is a circular relationship between the three, but one that is constructive and enlightening rather than destructive and self-defeating. “We are talking about appealing to the specific understanding of God that is derived from the prophets and apostles of Holy Scripture by means of exegesis. It is an appeal to the Holy Trinity. This means that a certain kind of circularity is inevitable in talking about a ‘Christian doctrine’ of anything – not a vicious circle, but rather an expanding circle of understanding” (33).

Further, I appreciate Carter’s informative and helpful survey of the crucial role and contributions of Christian Platonic thought throughout the history of the church. His advocacy of Christian Platonism appropriately defined and understood, as a paradigm for correctly understanding and applying the doctrine of God facilitates a better appreciation of the contributions of pre-modern biblical exegesis.

However, a concern and open question that remains is whether the metaphysics of all Christians of the pre-modern era can be accurately described as consistent with Christian Platonism or Ur-Platonism. Is it possible that this could be an oversimplification given other metaphysical perspectives evident during the era, such as Aristotelianism? Would Christian Platonism be consistent with the Christian Aristotelian perspective? Other reviewers have also identified these questions (among others) as open considerations.[4] In my mind, these questions still remain to be answered after reading Carter’s work.

Conclusion

In Interpreting Scripture with the Great Tradition, Craig Carter provides a powerful and helpful argument for retrieving the Great Tradition of Scriptural interpretation in the contemporary church. His work facilitates a rediscovery of the contributions of the great patristic theologians to biblical interpretation and celebrates the impact of their contributions throughout the history of the church. The work is refreshing, timely, and stimulating, and commended to pastors, church leaders and teachers, and academics seeking an interpretive approach to Scripture that celebrates Nicene Christianity and a Christ-honoring approach to reading, teaching, and preaching the Scriptures as the Word of God.

[1] “Dr. Craig Carter | Tyndale University,” accessed September 7, 2024, https://www.tyndale.ca/faculty/craig-carter.

[2] “Authors | Baker Publishing Group,” accessed September 7, 2024, http://bakerpublishinggroup.com/authors/craig-a-carter/836.

[3] “Dr. Craig Carter | Tyndale University,” accessed September 7, 2024, https://www.tyndale.ca/faculty/craig-carter.

[4] Chan-U Vincent Kam, “Interpreting Scripture with the Great Tradition: Recovering the Genius of Premodern Exegesis,” Concordia Journal 47, no. 4 (2021): 71–73; Isuwa Y Atsen, “Interpreting Scripture with the Great Tradition: Recovering the Genius of Premodern Exegesis,” Trinity Journal 41, no. 2 (2020): 218–20.

*Author’s note: an earlier version of this review was submitted by the author as a course requirement for DR 35090-F24E1 “Advanced Biblical Hermeneutics” at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary of Kansas City, Missouri.

One thought on “Resource Review: “Interpreting Scripture with the Great Tradition: Recovering the Genius of Premodern Exegesis” by Craig Carter”