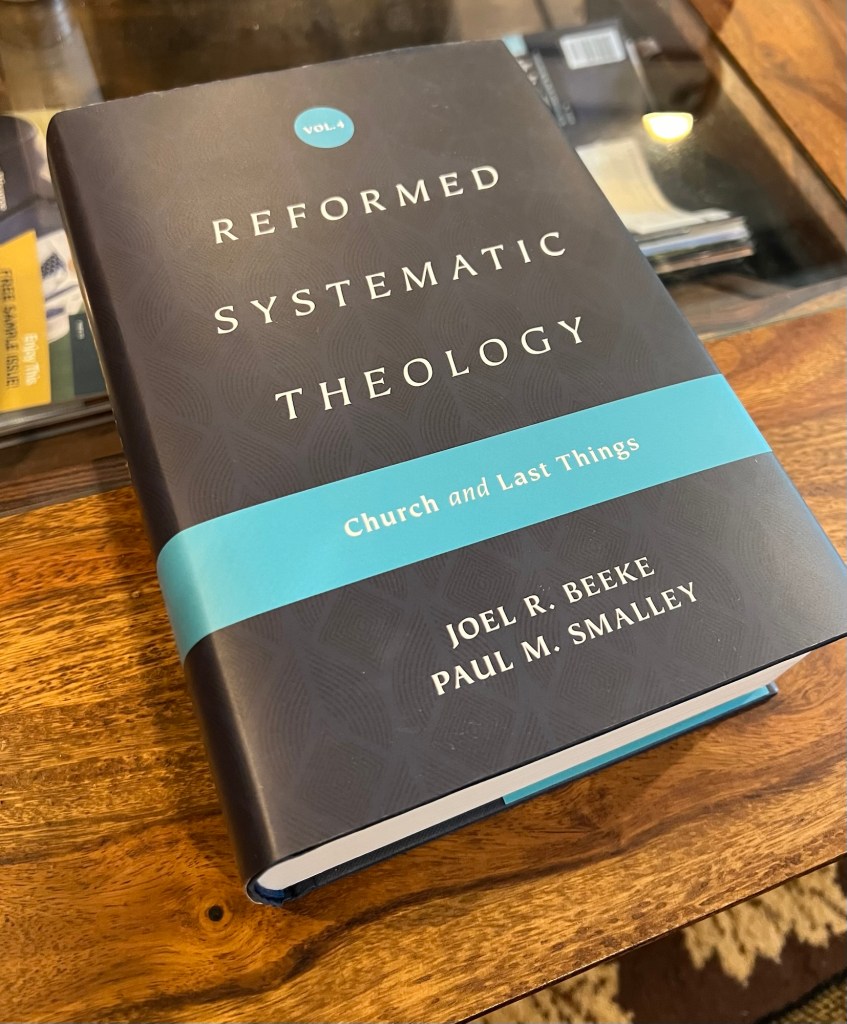

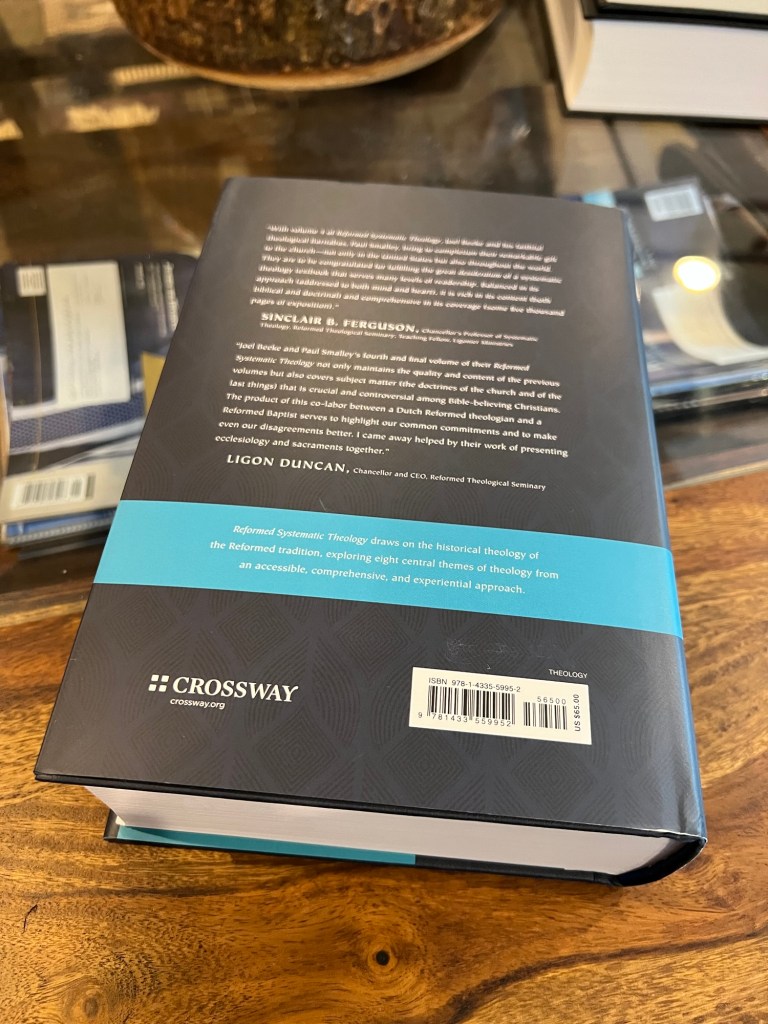

Beeke, Joel R. and Paul M. Smalley. Reformed Systematic Theology: Church and Last Things. Reformed Systematic Theology. Vol. 4. Wheaton, Ill: Crossway, 2024. ISBN: 978-1-4335-5995-2. $65.00.

Available From (click to access and purchase):

Crossway (the publisher; get 30% off or more by signing up for a free Crossway-plus account)

Overview:

In their fourth volume of Reformed Systematic Theology, Joel R. Beeke and Paul M. Smalley have furnished a magisterial treatment of the two final theological themes of their four-volume set: the doctrine of the church (ecclesiology) and the doctrine of last things (eschatology). The Reformed Systematic Theology work is a comprehensive systematic theology drawing deeply upon historical theology in the Reformed tradition. Volume 1, published in 2019, treated the doctrines of revelation and of God, while volume 2, released in 2020, examined the doctrines of man and of Christ. Volume 3, published in 2021, surveyed the doctrines of the Holy Spirit (pneumatology) and salvation (soteriology). The present volume completes this series with a contribution of breathtaking scope, power, and beauty.

Authorship/Editorship and Doctrinal Perspective:

Joel Beeke and Paul Smalley are both accomplished researchers, writers, and theologians. Beeke serves as chancellor and professor of systematic theology and homiletics (preaching) at Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary of Grand Rapids, Michigan, and pastor of Heritage Reformed Congregation of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Beeke has served in pastoral ministry since 1978. He received his Ph.D. in Reformation and Post-Reformation Theology from Westminster Theological Seminary. He is the editor of numerous publications, including Puritan Reformed Journal and The Banner of Sovereign Grace Truth Magazine, and has been active in book publishing through service as Chairman of the Board of Directors of Reformation Heritage Books, president of Inheritance Publishers, and vice president of the Dutch Reformed Translation Society. Beeke is also a prolific author, having written and contributed to more than 120 books, as well as having edited over 100 works and contributed more than 2,500 articles to various books, journals, periodicals, and encyclopedias.[1]

Paul Smalley serves as research assistant to the chancellor at Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary and as a pastor at Grace Immanuel Reformed Baptist Church of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Before assuming his role at Grace Immanuel, Smalley also served twelve years as pastor of other Baptist churches in the midwestern United States. Smalley received his Master of Divinity degree from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School of Bannockburn, Illinois. In addition, he received his Master of Theology (Th.M.) degree from Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary, from which he also received an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree.[2]

Materials and Construction:

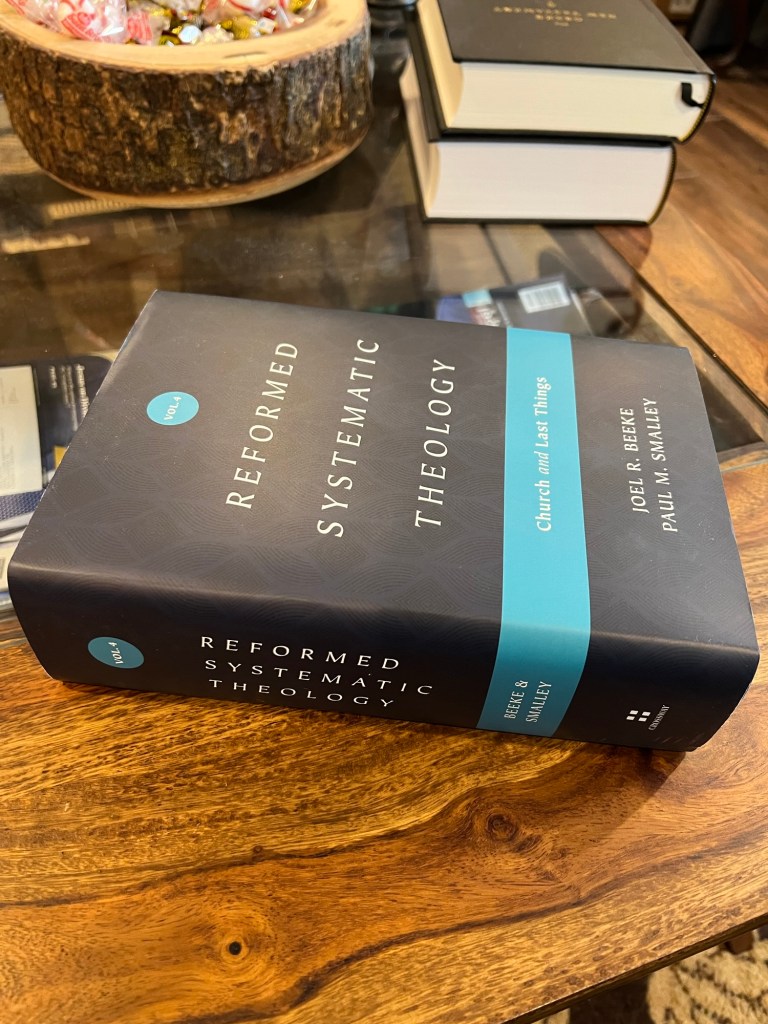

Consistent with virtually everything Crossway publishes, the work reflects beauty in its design and quality in its materials and construction. The work is set in a durable hardback binding and is Smyth-sewn – a vitally important feature for durability, given the book’s voluminous 1,360 pages of content. Beneath the relatively simple, yet stylistically pleasing dust jacket, the hardback binding is textured with a dignified gold embossing of the work’s title, authorship, volume number, and publisher on the spine.

The physical page quality of the work is strong, with minimal ghosting. In addition, the work is formatted with sufficient, if not generous, margin space throughout. The 3/4” margins allow the reader to comfortably make notes and annotations throughout the work. They are a distinguishing feature from some other systematic theologies that furnish more concise margins. For example, Adam Harwood’s excellent Christian Theology, published by Lexham, is formatted with a 5/8” margin. Such a slight difference might not seem significant initially, but for readers who annotate their books – especially scholarly works – even an extra 1/8” of margin space makes a meaningful difference and adds up.

As an aside from this review, if you are bibliophile (book-lover) who hesitates with regard to whether to mark-up your books with personal notes or annotations or if you’re a reader who simply wonders why others do this, Dr. Albert Mohler provides an excellent discussion of this in his book, The Conviction to Lead: 25 Principles for Leadership That Matters. In Chapter 12, entitled “Leaders Are Readers,” Mohler posited,

“Learn to read critically. Reading is not merely an exchange of information and ideas. It is a conversation between the author and the reader. Think of reading as a silent but intensive conversation. As you read, ask the author questions and filter the book’s content through the fabric of your convictions. Argue with the book and its author when necessary, and agree and elaborate when appropriate. Treat the book as a notepad with printed words. In other words, write in your books. Make the book your own by marking points of agreement and disagreement, highlighting particularly important sections of text, and underlining and diagraming where helpful. Unless your specific copy of the book has some historical or emotional value, mark it up with abandon. The activity of marking your books adds tremendously to the value of your reading and to your retention of its contents and your thinking. I can go back to a book I read a half century ago and reenter my experience of reading that book for the first time. My notations and remarks make this possible. Often when I reread a book I read many years ago, I am struck by how I read it somewhat differently now, marking different passages and asking the author different questions.”[3]

As a pastor and professor who reads constantly as part of my ministerial and professional responsibilities, I couldn’t agree more with Dr. Mohler’s assertions. If you want to enhance your reading experience and retention of what you read, annotate your books – or at least take notes from them. For another excellent discussion of highlighting, underlining, and making notes in your books, check out Chapter 5 of Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren’s work, How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading, entitled “How to Be a Demanding Reader.”[4]

Survey of Contents:

The work opens with a helpful list of abbreviations used throughout the book (pp. 13-16), followed by a listing of tables included (p. 17). A preface to Volume 4 of Reformed Systematic Theology is then presented (pp. 19-22). The preface provides helpful insights related to the nature of volume 4, the authors’ immense gratitude to each other, as well as others that provided help and assistance in the creation of the volume, and above all, a tribute to the grace of God and a prayer for Him to invoke the work to His glory and for the good of His church. The authors noted, “It is our hope and prayer that, by God’s grace, Reformed Systematic Theology will take its place among the many theological works that prove to be edifying to the church of Jesus Christ…If you, the reader, benefit in any way from our work, please do what you can to spread these great truths, so that by the grace of God others may know, love, and serve God in obedience to his holy will. That grace-empowered, heart-quickening, life-transforming, experiential knowledge is the true theology given to us through Jesus Christ. Soli Deo gloria!” (p. 22). I can’t think of a more fitting way to preface a systematic theology, and such a tribute to the grace of God and prayer for His use of the work is especially fitting given that this volume is the final installment of the four-volume work.

As the title implies, the book is divided into two major sections. The first half of the work is dedicated to ecclesiology (pp. 25-685), while the second half treats Christian eschatology and related subjects (pp. 689-1152). The volume consists of 42 chapters in total, with chapters 1-25 dedicated to “Part 6: Ecclesiology: The Doctrine of the Church,” while chapters 26-42 treat “Part 7: Eschatology: The Doctrine of the Last Things.” In addition to the listed chapters, the book also includes several excursuses that provide fascinating and in-depth explorations of particular issues that are given a more summative treatment or reference in preceding chapters. As I’ll discuss more in a moment in the critical evaluation section of this review, an excursus I found particularly helpful and fascinating treated the topic of “Theological Professors or Doctors of Theology” in the church (321-336).

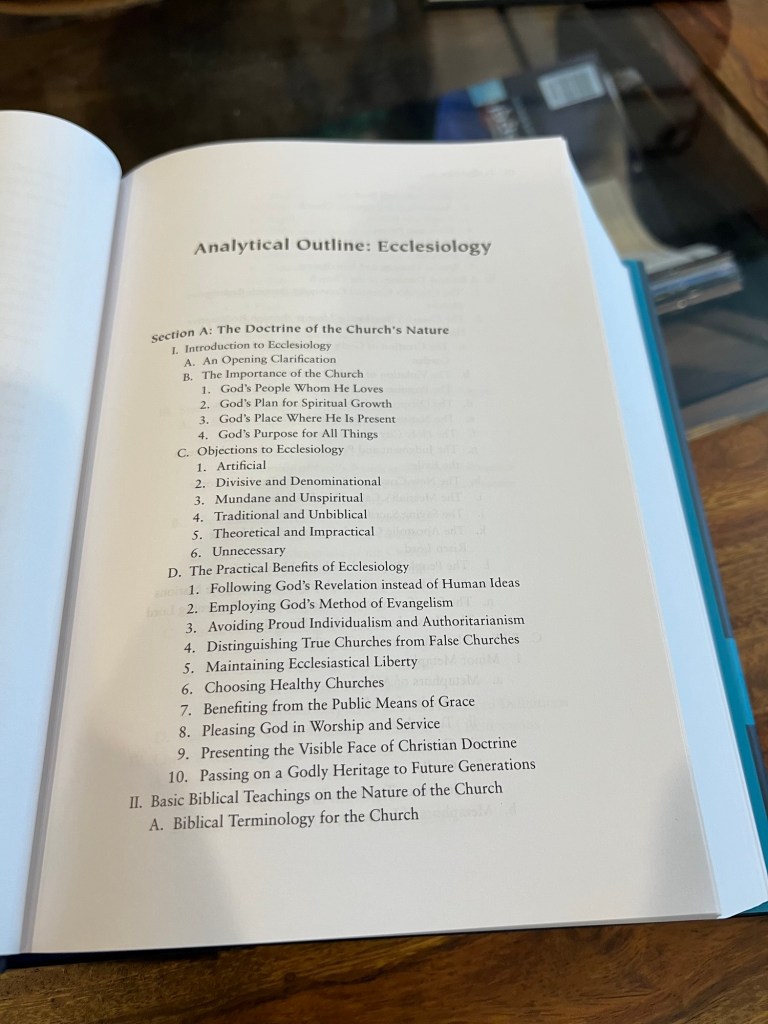

Both parts begin with a comprehensive analytical outline of each major theological subject and its various components treated throughout the work. The detailed analytical outlines alone are enormously valuable, particularly for pastors, teachers in the church, and professors in the seminary or academy planning to teach and lead studies of these enormous, yet crucial, subjects. Each of the two major parts of the work is further subdivided into sections. Within Part 6 (Ecclesiology), the content is divided into “Section A: The Doctrine of the Church’s Nature” (47-214), “Section B: The Doctrine of the Church’s Authority and Work” (215-454), and “Section C: The Doctrine of the Church’s Means of Grace” (455-685). Part 7 (Eschatology) is organized into “Section A: Preliminary and Special Issues in Eschatology” (707-936) and “Section B: The Doctrine of Hope in Christ Alone” (937-1152).

Within each chapter, the text begins by providing a brief introduction to the topic treated by the chapter, followed by the chapter content. The authors made abundant use of headings and subheadings throughout, which makes the work very well suited as a reference resource and enables the reader to navigate the chapter content, as well as the arguments articulated by the authors treating various subjects within each chapter, clearly and effectively. Towards the conclusion of each chapter, the authors provided a summative “applications” section that helps the reader to understand the importance of the topic(s) treated within the chapter and how to live out the theology explored in a practical sense within the Christian life. Following this application section, the work continues to emphasize the importance of Christians living out the deep theological truth examined within by including a hymn related to the chapter’s content. For example, at the conclusion of Chapter 4, “Systematic Theology of the Church’s Nature,” the authors included the lyrics of the hymn “Psalm 84” from The Psalter, No. 227, set to the tune “St. Edith.” Personally, I love this feature, as it emphasizes the importance and enduring power of worship rooted in deep theological truth, as well as the living and devotional nature of the theology explored in each chapter. The reader should also note that the hymns at the end of each chapter include lyrics only, and while referencing the related tune to which the hymn is set, do not include sheet music.

Following the hymn emphasizing worship of the Lord through praise and celebration of His truth, the chapter concludes with two sets of reflective questions provided by the authors related to the chapter’s content. The first set, entitled “Questions for Meditation or Discussion,” provides questions designed to provoke foundational reflection and meditation on the theological topics treated in the chapter. The second set, “Questions for Deeper Reflection,” is typically fewer in number, but facilitates deeper thinking on the topics presented. Both sets of questions are of enormous value for those using the work as a teaching resource, as well as for engaged readers seeking to think and reflect more deeply on what they’ve read and considered in each chapter.

The work contains an abundance of footnotes throughout, emphasizing its scholarly character and its value as an academic reference. The work contains a total of 4,258 footnotes across the introduction, 42 chapters, four excursuses, and the appendix, with an average of approximately 91 footnotes per chapter. The footnotes are written in Chicago Style, which makes them particularly helpful for the scholarly reader seeking 1.) to clearly identify the authors’ research and basis for their points and arguments, and 2.) to identify resources for further study and research related to the topics considered.

The volume concludes with an appendix articulating a Reformed Baptist perspective on the subjects and mode of Baptism (pp. 1153-1183). This appendix is specifically representative of the perspective of Paul M. Smalley as the second author, who hails from a Reformed Baptist perspective in his theology. Following this appendix, the work provides a robust bibliography of works and resources utilized throughout (pp. 1184-1250), as well as a general index (pp. 1251-1278) and Scripture index (pp. 1279-1360).

Critical Evaluation:

As the final contribution to what is arguably Beeke and Smalley’s magnum opus, Volume 4 of Reformed Systematic Theology does not disappoint. The book is enormous – both physically (at more than 1,300 pages) and in terms of its content and caliber of scholarship. As alluded to earlier, the volume is thoroughly and meticulously researched, as evidenced by the abundance of footnotes and the interactions with various perspectives, arguments, and positions on the theological subjects within ecclesiology and eschatology treated throughout.

As the name of the overall work implies, both authors write from a Reformed theological perspective, albeit with an interesting degree of theological diversity between them. While Beeke hails from the Heritage Reformed denomination, Smalley represents the Reformed Baptist perspective. The Heritage Reformed Congregations (HRC) denominational movement is deeply influenced by English Puritanism. The HRC is also a member of the North American Presbyterian and Reformed Council (NAPARC). The Reformed Baptist tradition represented by Smalley is briefly summarized as holding to a Reformed theology in general with a Baptist ecclesiology. Given Beeke’s role as the lead author, the reader of this work should keep in mind that the chapters are largely written from his doctrinal perspective (with important acknowledgments, footnotes, and an appendix treating Smalley’s views on points where they differ). Beeke’s HRC convictions are particularly prominent in the first half of the work, treating the doctrine of the church.

An important point for life, learning, and scholarship is that we can benefit much from reading the thoughts, positions, and arguments of those with whom we disagree. The reader of this review should note that I come from a traditional Southern Baptist theological perspective. Accordingly, I do not hail from the same denominational traditions as the authors, and my theology is marked by several significant differences with theirs, especially in their views of church governance and polity, Baptism and the Lord’s Supper, and interpreting the book of Revelation.

My personal theological convictions and those of the church I pastor are concisely reflected in the Baptist Faith and Message (2000). In addition, my prior (and future) blogs articulate my theological positions on a variety of ecclesiological and eschatological matters, so I won’t exhaustively articulate my differences in theological position and reasoning with the authors of Reformed Systematic Theology in this review. However, for the purpose of informing prospective readers, surveying some of the major topics treated in the work, and providing a disclaimer of sorts attached to my general commendation of this volume, a concise summary of some of the most important points with which I differ from the authors as a Southern Baptist is as follows.

With the exception of the appendix and certain points made in various footnotes throughout, this work argues in favor of what most would identify as a Presbyterian system of church government. Beeke and Smalley label their view taken on eldership and church government as representing “Reformed and Presbyterian” convictions (p. 268). In contrast, as a Southern Baptist, I believe in congregational church government in which the membership of the church, rather than a ruling body of elders, holds responsibility for making major decisions as the locally gathered body of Christ. In a congregational system of governance, pastors lead local bodies of the Lord’s church in the decisions they make and the actions they undertake. For a helpful treatment of congregational church government from a Southern Baptist perspective, check out Jonathan Leeman’s Don’t Fire Your Church Members: The Case for Congregationalism.[5]

I also affirm two offices in the New Testament church (pastors and deacons) and believe that the terms “pastor” (Greek: ποιμήν), “elder” (Gr: πρεσβύτερος) and “overseer”/“bishop” (Gr: ἐπίσκοπος) refer interchangeably to the same New Testament office that is commonly – and appropriately – called “pastor.” I do not believe there is a valid New Testament distinction between “ruling elders” and “pastoring or preaching elders/ministers of the Word.” In contrast, the authors of this work argue in favor of either a three-fold or four-fold model of church offices. The reader should note that “either” doesn’t imply confusion on my part as to what Beeke and Smalley believe, but instead represents Beeke’s position that at least a threefold model of offices should be affirmed – and preferably a fourfold model. The authors observed in footnote 28 in Chapter 9, “Church Officers: Part 1,” that, “Joel Beeke favors either the four-office view (ministers, professors, ruling elders, and deacons), in accord with Calvin and the Synod of Dort, or the three-office view (ministers, elders, and deacons, with professors being a subset of ministers). Paul Smalley favors the two-office view (elders and deacons), though with the qualification that only some elders are gifted to preach, the ministers of the Word being a category of giftedness and service that is distinct from but overlapping with the elders” (p. 263). Thus, the threefold model articulated by the authors holds that the New Testament church offices consist of ministers of the Word (pastors or elders who both preach/teach and rule), elders (basically pastors who do not preach and teach but are involved in the ruling function under the Presbyterian paradigm), and deacons. The fourfold model includes these three offices and adds a fourth of “teacher” or “doctor of the church” (one responsible for teaching and training ministers of the word – i.e., seminary professors).

Further, this systematic theology advocates in favor of paedobaptism (the baptism of infants and young children). As a Southern Baptist, I reject paedobaptism and instead affirm believer’s baptism (baptism following a conscious public profession of faith on the part of a follower of Jesus). In addition, the authors argued in the body of the work (with exceptions noted in the footnotes and the accompanying appendix) in favor of baptism by a variety of modes (including immersion, sprinkling, and pouring). As a Southern Baptist, I affirm baptism by immersion only.

Additionally, as a Southern Baptist, I hold to what is often described as a memorialist view of the Lord’s Supper (the elements of bread and the fruit of the vine are symbolic representations of the broken body and shed blood of Christ). The authors provide a helpful and informative treatment all of the major views of the Lord’s Supper according to how various groups of Christians understand Christ to be present at or in the supper, including the “real, undefined presence” represented in the early church (577-579), “real, bodily presence by transubstantiation” (held by Roman Catholics, pp. 579-580), “real bodily presence by sacramental union” (held by Lutheranism, p. 581), “real spiritual presence by the Holy Spirit” (representative of the Reformed position held by the authors, pp. 582-583), and the “memorial without any promise of special presence” view (how the authors described memorialism as held among Southern Baptists and other groups of Christians, pp. 583-584). The authors advanced a robust and detailed argument in favor of the “real spiritual presence” position in pages 584-593).

Moreover, regarding eschatology, the authors surveyed the major interpretive schools on the Revelation (preterism, historicism, idealism, futurism, and eclecticism) and endorsed the eclectic position, which combines elements of the first four interpretive positions (pp. 847-852). While I have some sympathy with eclecticism depending on how it’s defined and articulated, my own interpretive convictions on Revelation (described using the often more familiar terms “premillennial” and “pretribulational” and articulated in depth in a previous post) would be categorized by most as falling into the futurist camp.

In terms of the overall approach, the authors did an excellent job of showcasing Scripture and their arguments from Scripture first and foremost throughout each chapter. In addition, the authors interacted deeply and regularly with various voices throughout the history of the church that help us to think about and understand Scripture – an approach I deeply value and appreciate as a historical theologian. The authors regularly engaged with a variety of theologians (including both prominent and some less well-known but no less important voices) from virtually every era of church history, as well as the positions, actions, statements, and impacts of an array of historical figures influencing the development of ecclesiology and eschatology (including figures such as Charlemagne, Elizabeth I, Thomas Jefferson, Napoleon, Karl Marx, and Adolf Hitler). Further, the authors examined a variety of important confessional statements representing various eras of church history that shaped and made crucial contributions to the church’s understanding of the doctrines of the church and last things. Accordingly, the arguments in and content of the book are broadly well-sourced and reflect a comprehensive appeal to both biblical and historical support.

A notable and helpful attribute reflected throughout the work is the pastoral concern and tone set by the authors in their robust treatment of the topics covered. From beginning to end, Beeke and Smalley wrote with a steadfast desire to glorify God and edify the church. Even in reading sections of the work articulating positions or arguments with which I personally disagree, I found the authors’ concern for the glory of Christ and the health and strength of His church to shine through every argument presented and every topic expounded.

For example, in their discussion of church officers in Chapter 9, the authors posited from the beginning that a strong theology of church leadership and the New Testament church offices is necessary for the health of Christ’s church. The authors observed, “The Lord Jesus governs his church through officers whom he gifts and calls into ministry by the Holy Spirit working through the Word. John Calvin said, ‘While God could accomplish the work entirely himself, he calls us, puny mortals, to be as it were his [assistants], and makes use of us as instruments.’ The impact of church officers is incalculable, whether for good or ill. Greg Nichols says, “Scripture reveals that God deals with his people in such a way that leadership is key to their blessing or to their moral failure” (p. 257). Crucially, the authors also rooted their theology of church leadership firmly in the concept of divine calling. “Church officers are not simply competent people who work in the church; they are appointed and given by God (Acts 20:28; Eph. 4:11)” (p. 258). The divinely-called nature of church officers is a crucial component of correctly understanding both what they are to do, how they are do it, and why they are to do it.

This pastoral tone, concerned for the welfare of the Lord’s church, also contributed to the practical observations advanced by the authors. Any Christian who has been meaningfully involved in the life of his or her local church will recognize that faithful service in any office of the church demands a set of God-given and Christ-honoring skills. Pastoral ministry demands a particularly formidable array of skills and resources. As fallen human beings, even the most faithful of Christians serving as church officers can become discouraged and overwhelmed by a feeling of inadequacy for the calling given to them. And again, this is especially true of pastors. Of this, Beeke and Smalley wisely observed, “Whenever an officer finds himself lacking the resources necessary to fulfill his office, he should not despair but look to Christ in prayer for the supply of the Spirit and press on in faithful obedience” (p. 258). In response, I can only say “amen.” “Press on” is a Scriptural exhortation (Phil. 3:14) vital to all Christians and one which I increasingly find to be needed and encouraging as a pastor.

The concern for the health of the church is even reflected in the work’s treatment of the academy. In the aforementioned excursus exploring the fourth church office identified by the authors – that of “teacher,” “professor,” or “doctor of the church” (references used interchangeably) – the authors emphasize the crucial nature of the ministry of academically preparing ministers for the health, vitality, and future of the church. In this excursus, the authors provided a fascinating historical survey of the church’s understanding of the role of teachers and professors of theology and ministry. Beeke and Smalley introduced the topic by observing, “Teachers must train other teachers if the didactic ministry of the church is to continue and expand (2 Tim. 2:2)” (p. 321). The authors continued, “Christ’s mandate to make disciples of all nations, teaching them to obey all his commands, implies that the church must be training teachers to serve every community in every generation to the end of the age (Matt. 28:19-20). All ministers of the Word should seek to encourage and train potential teachers, but the work of training future ministers normally falls upon a group of specialized teachers known as theological professors or doctors of theology, who work at schools known as seminaries.” (p. 321).

In this same excursus, the authors also advanced a powerful argument articulating the need for seminaries and the faculty who serve them in preparing future pastors, missionaries, and other church leaders. In the concluding reflections of this excursus, the authors posited, “Professors of theology have played a crucial role in Reformed Christianity from the sixteenth century to the present time…the church needs teachers who can train ministers and teachers. Humanly speaking, the church is always a few generations away from extinction. Christ maintains his church on earth by continually raising up new gospel laborers…most full-time ministers pastoring congregations do not have the time…to provide a complete ministerial education. As we noted in the previous chapter, the ministers of the Word have great demands placed upon them in their faithful preaching, teaching, and leading. While they can mentor others, how can they be expected to give them a thorough education in Greek, Hebrew, exegesis, systematic theology, Christian history, preaching, and pastoring? The nature of training other teachers calls for professors set apart for this task and allowed to specialize – for how many people are prepared to teach all these subjects?” (335).

The authors also provided a particularly helpful analysis of the concept of calling in Chapter 10, examining “Ministers of the Word.” The authors advance a threefold understanding of calling to pastoral ministry, arguing in favor of a model that reflects 1.) a divine call (pp. 291-292), 2.) an internal call (pp. 292-294), and 3.) an external call (pp. 294-298). Particularly powerful and, in some ways, unique to this volume as a systematic theology is Chapter 11, “Church Officers, Part 3 – The Faithfulness of God’s Ministers” (pp. 300-320). Beeke and Smalley highlighted the absolutely essential nature of pastoral faithfulness from the outset of this chapter. “A minister, by the very definition of the term, is a servant…The faithfulness of ministers is crucial for the life of the church. Paul commands elders, ‘Take heed therefore unto yourselves’ (Acts 20:28), and exhorts the minister, ‘Take heed unto thyself, and unto the doctrine; continue in them: for in doing this thou shalt both save thyself, and them that hear thee’ (1 Tim. 4:16). The last words in Paul’s statement are sobering: a faithful ministry is one of God’s great means to bring his people through all their trials and temptations to receive full and ultimate salvation by grace” (p. 300).

In their treatment of eschatology, the authors not only surveyed the typical topics related to the doctrine of the end times (including interpretive schools on the book of Revelation, bodily death, the second coming of Christ, the resurrection of the dead, the Day of Judgment, eternal punishment in hell, and eternal life with God in Christ), but also provided a helpful treatment of non-Christian views on eschatology in their introduction to the doctrine in Chapter 26. Under the heading “The Hopes and Expectations of the World” (pp. 708-718), the authors summarize the views of various world religions on the future of humanity and creation before advancing well-articulated Christian responses to those views. The non-Christian views surveyed include African traditional religions, popular Western culture, Hinduism, Buddhism, Daoism (or Taoism), pagan religion (Norse mythology), atheism, biological evolution, Marxism, panentheistic social progressivism, optimistic technological futurism, environmental catastrophism, transhumanism, Judaism, and Islam. The summary of each of these views is helpful in itself, but even more so are the authors’ responses to those views from a Christian perspective. This section will be especially helpful to Christians seeking to witness to and engage friends and connections representing these various perspectives with the Gospel.

Summary and Recommendation:

While I differ with the theological convictions of Beeke and Smalley in several respects, Volume 4 of Reformed Systematic Theology is a monumental contribution to the theological literature examining ecclesiology and eschatology. The work is a triumph of theological scholarship on the part of the authors, founded in a deep-seated desire to honor and serve the Lord and advance His church. It is to be commended to any Christian looking to deepen their knowledge and understanding of the doctrines of the church and last things, and will be a valuable addition to the libraries of pastors, teachers, church leaders, and followers of the Lord Jesus seeking to more deeply understand the truth of Scripture.

*Author’s note: I received a copy of this book from Crossway in exchange for an honest review.

[1] Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary, “Dr. Joel R. Beeke,” “Faculty,” prts.edu. https://prts.edu/profile/joel-beeke/; Crossway, “Joel Beeke,” “Authors,” crossway.org, https://www.crossway.org/authors/joel-r-beeke/

[2] Grace Immanuel Reformed Baptist Church, “Meet our Pastors,” “About Us,” girbc.org, https://www.girbc.org/about-us/; Crossway, “Paul M. Smalley,” “Authors,” crossway.org, https://www.crossway.org/authors/paul-m-smalley/

[3] R. Albert Mohler, Jr., The Conviction to Lead: 25 Principles for Leadership That Matters (Bloomington, Minnesota: Bethany House Publishers, 2012), 101-102.

[4] Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren, How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent Reading (New York: Touchstone, 2014), 45-58.

[5] Jonathan Leeman, Don’t Fire Your Church Members: The Case for Congregationalism (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2016).